A Strategic Way to Make Sense of New Topics

At a glance

- Based on the reader question: When problem-solving, how do I make sense of new topics efficiently? – Leo, UK

- Learn how to efficiently understand a new topic and develop an informed opinion using two simple but enduring principles: 1) General to Precise 2) Quit or Carry On.

- Reinforce your understanding of the techniques by seeing how they work together to overcome the demanding task of writing an Oxford essay in 3 days. View the essay as a proxy for whenever you need to find a solution to a complex problem whether it be for your studies or career.

Introduction

One of our unacknowledged daily rituals is making sense of new topics. We're constantly capturing information, connecting dots and creating things based on our understanding of what's most likely to lead to our preferred outcome: trying to win a legal case, launching a new business or growing our first bonsai tree. In sum, there is a problem and we must find a solution.

With sense-making being an essential part of making the most of our studies and careers, we've made it the focus of today's guide. We'll share two simple but enduring principles that will allow you to sense-make and learn efficiently, develop more thoughtful positions and make judgements that are more likely to lead to your preferred outcome.

The two foundational principles for doing this are:

- General to Precise

- Quit or Carry On

So you can see these principles in action, we'll share our workflow for tackling one of the most hated of tasks: writing an essay. Specifically, an Oxford essay.

If you hate essays, don't be put off. It's simply the best way for us to illustrate how to efficiently sense-make, as essay writing demands that we research a topic and then provide a precise answer to a question.

In that way, it echoes our other sense-making rituals: there is a problem and we must offer a solution, making it a valuable showcase of how to use the principles to tackle any topic that you need to understand.

The Oxford University pressure cooker

At the University of Oxford, humanities undergraduates are tasked with writing two 2,000 word essays every week on topics they've never studied before. That gives students three days to go from knowing nothing about a topic to digesting long reading lists and producing a thoughtful answer they can defend in front of their professors. Once done, the sense-making cycle repeats for the next essay.

It's in that pressure cooker that our sense-making workflow was tried and tested before being adapted for the workplace, a space that also requires us to make complex decisions on tight deadlines.

The two sense-making principles explained

General to Precise

We learn faster when we introduce ourselves to a new topic by building up a general picture first and then moving onto the material that will give us a more precise understanding of a topic's nuances.

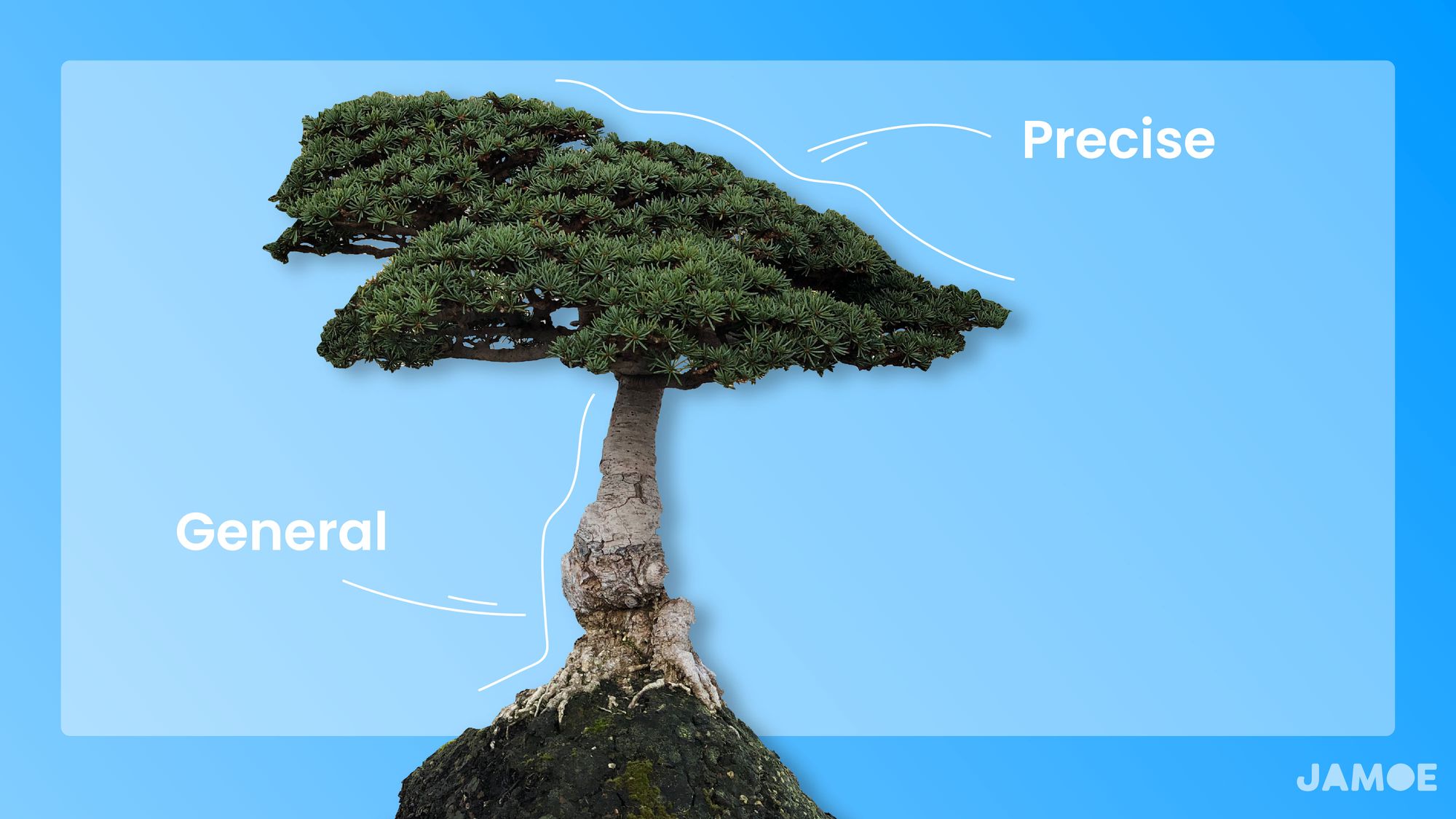

Trees are a valuable guide when it comes to explaining the intuition behind the General to Precise principle. Looking at a tree, you can break its structure down into three parts: the trunk, the branches and the leaves.

Without branches, the leaves would fly away in the wind; without the trunk the branches would fall on top of the person reading their book below. Realising this reveals why it's easier to start with a strong general understanding, as it gives the leaves and the branches something to latch onto making these new bits of information easier to understand and remember.

In the example below, we'll provide some low-effort but high-value recommendations you can use when building up the trunk of your knowledge tree. To make it more practical, we'll be answering the essay question, 'Should the minimum wage be abolished?'.

This principle also crops up in our techniques for Understanding What You're Reading Faster and our Practical Workflow for Efficient Note-taking, making it something to learn once and use forever.

Quit or Carry On

Never give up and never give in is a deeply unhelpful mantra when reading to make sense of a new topic. Sometimes reading is a joy, other times it's a medicine. However, once our health has been restored and we've finished our course, it would be unwise to carry on popping pills. The same is true of continuing to read a book that has fulfilled its purpose. Reaching this milestone is when we should quit and save ourselves hundreds of pages worth of time, even if that means swallowing the discomfort of stopping halfway.

Knowing when to move on relies on us reading with a purpose. When sense-making, our purpose is to understand a problem and find an adequate solution. Our guide for ensuring we stay on a purposeful path is the Quit or Carry On principle, as it, like any good guide, keeps us on track and away from dead ends and stinky alleyways.

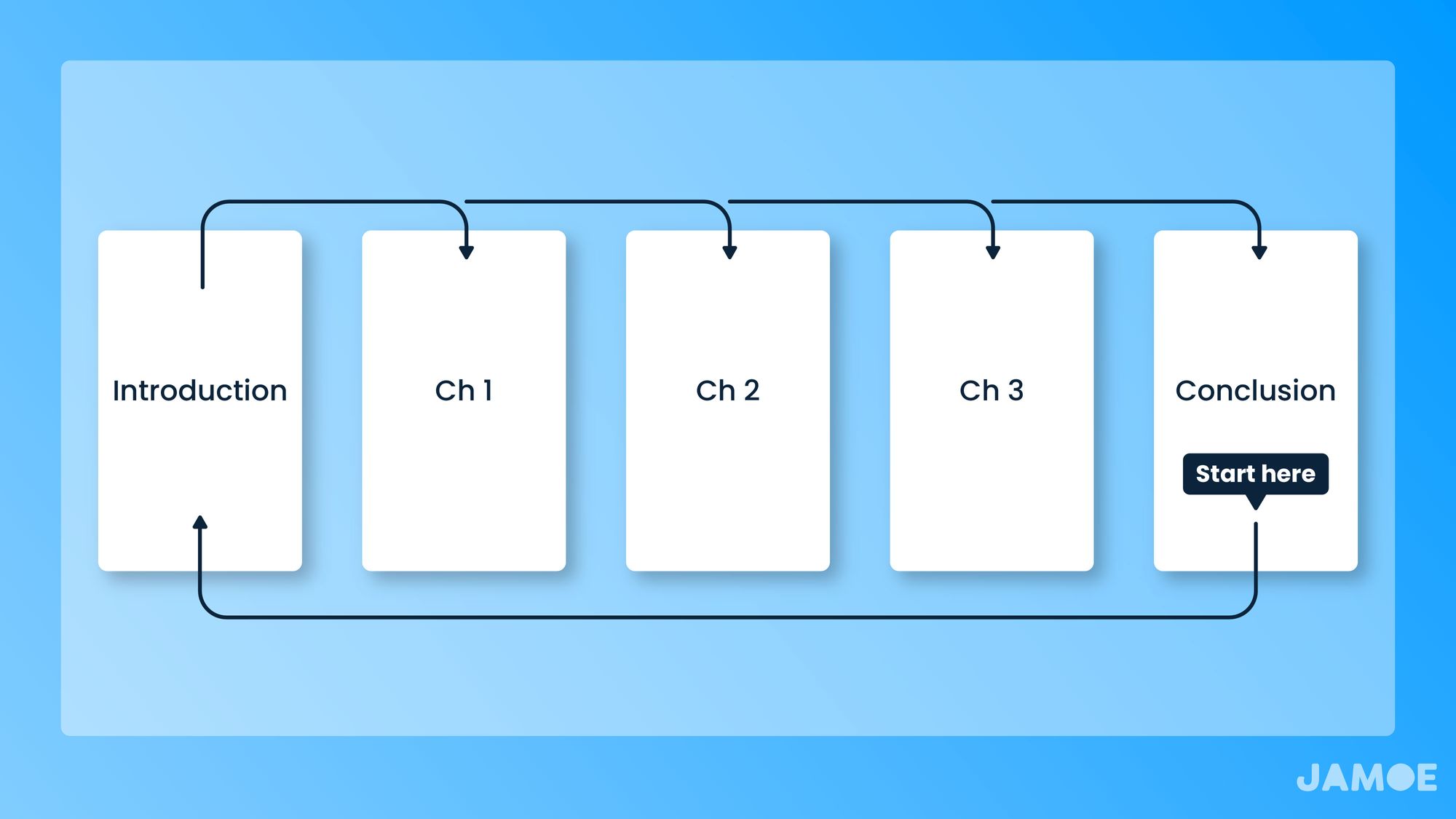

When reading to make sense of a topic, there are some natural checkpoints we can use to decide whether we should Quit or Carry On. They exist in every text and neatly overlap with our End-Beginning-Middle workflow for understanding what you're reading faster. We'll explain what this is in a moment.

Using this approach when making sense of a new topic is the difference between trying to find a needle in a haystack, and knowing, before you start, whether there even is a needle.

A general application of the two principles when reading

Checking if a book is worth your time

Often we don't have a perfect reading list waiting for us when solving unfamiliar problems, so we have to be sceptical readers and exercise the default mindset of a despotic ruler: every page is guilty of being useless until proven innocent.

In practice, that means asking ourselves, 'Is reading more going to be the most honest way of solving the problem?'. Using the answer, we can then decide if we should Quit (and read something else) or Carry On.

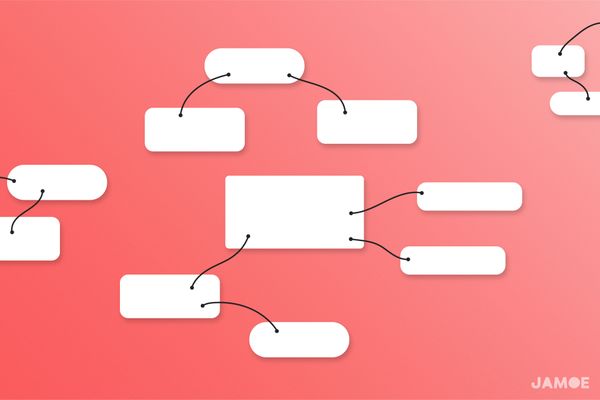

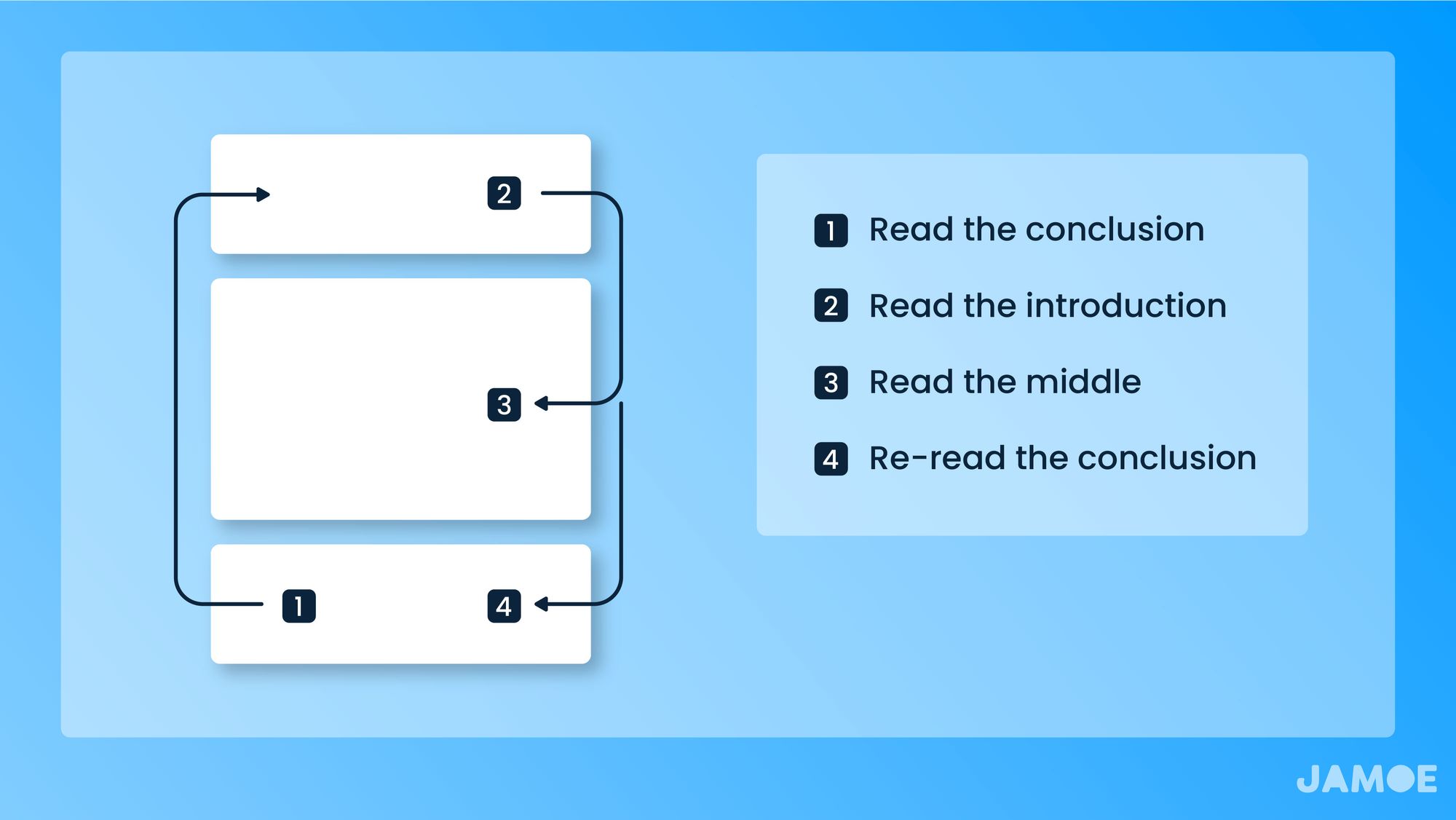

The End-Beginning-Middle approach helps us do this efficiently. By reading the conclusion first, we can build up a general understanding of an author's argument. If it sounds promising, investing more time reading the introduction wouldn't be a bad move. We can then repeat this thought process before committing to reading the main body of the text.

As you'll see in the essay writing example below, it's a versatile approach that allows you to move from confusion to clarity on a deadline by efficiently extracting value from books, academic articles, blogs, newspapers and reports.

Checking if a chapter is worth your time

Thinking more strategically, you can use the Quit and Carry On principle to judge which chapters are going to be the most helpful. That way, you can shortcut to Chapter 7 instead of worrying about the irrelevant details in the previous six chapters.

It's the exact same workflow as before, but applied at the chapter-level. Read the conclusion, then the introduction, then skim the main body until you find the key nuggets for solving the problem you're tackling.

If the book has a contents or an index, you can use this to help you locate the best chapters to start with. There's a bit of guess work involved, but using these tools will help you stack each guess in your favour and spare you the expense of reading irrelevant books cover to cover.

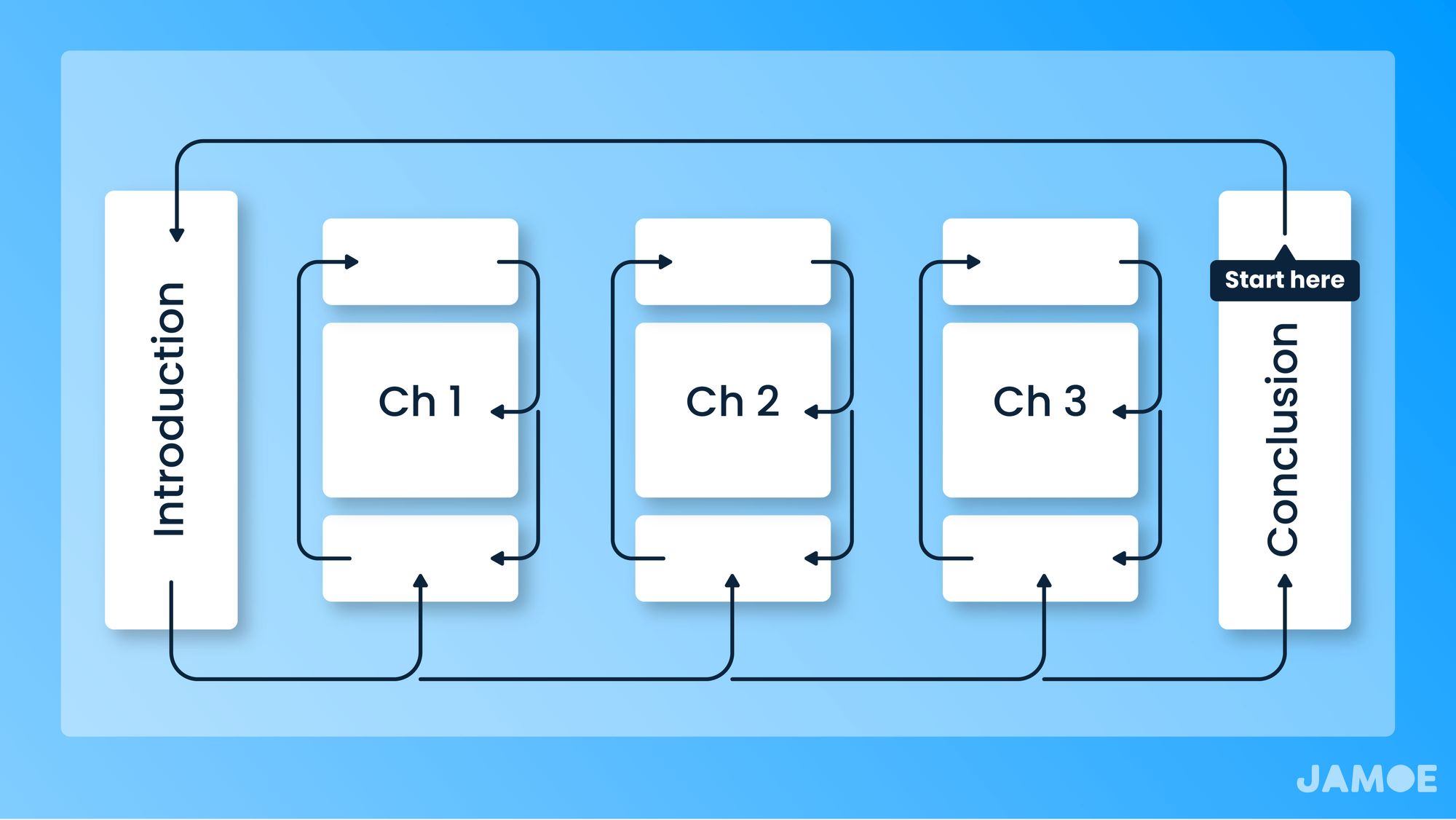

Reading the Perfect Book: Combining Quit and Carry On with End-Beginning-Middle

The perfect book is a relentless source of guidance to help you solve the problem you're working on. We've sketched the workflow of a reading such a book below.

In reality, you should reserve the right to abandon ship and move onto the next item on your list. Efficiency demands focus, and having a strong filter is one of the best ways to sort the glitter from the gold.

Applying the strategy to writing an Oxford essay

The essay question: abolishing the minimum wage

We've chosen the essay question, 'Should the minimum wage be abolished?'. Our knee-jerk reaction was to say, 'No, it shouldn't be abolished'. However, we'll probably learn more by taking the opposite side of the argument and thinking through the circumstances that would need to be true for us to convincingly argue for the minimum wage's abolishment.

Forcing ourselves to take a position at the start will make us more attentive when researching, as we'll be primed to see if our guess is defensible or needs revising. It's similar to how scientists amend their guesses when they prove to be poor explanations for natural events. The opposite of doing this is reading passively. It's far slower and isn't recommended.

Using this approach, we'll use the following as a starting point for our argument:

Yes, the minimum wage should be abolished. Rising automation is set to bring about a wave of unemployment, and the minimum wage is no comfort to those without a job.

We'll now see how this holds up when we start investigating the problem using the General to Precise and Quit or Carry On principles.

Applying the General to Precise principle

Building up a general understanding of a topic is best done by using easy to digest sources of information. These kinds of sources have a low time commitment and don't require huge amounts of preexisting knowledge. Once done, you can then be more strategic when consuming longer and denser sources of information.

This is also a more joyful way to make sense of new topics. We say in Learning to Hate Fiction, 'Read what you love until you love to read'. The same is true here. By starting with the low-effort (and far more engaging) sources of information – Tweets, YouTube videos, Podcasts – you'll develop a genuine curiosity for the topic and use it to overcome yourself.

For example, if you want to understand the key historical details of The Mongol Empire you could find a 10-minute video summary online, then search for a podcast, before flicking through a children's book on the topic. You'll end up with a gaggle of questions that will peck at your mind and turn it into a sponge that wants to know more. With that vantage point, you'll be able to decide if reading more academic texts would be a good investment.

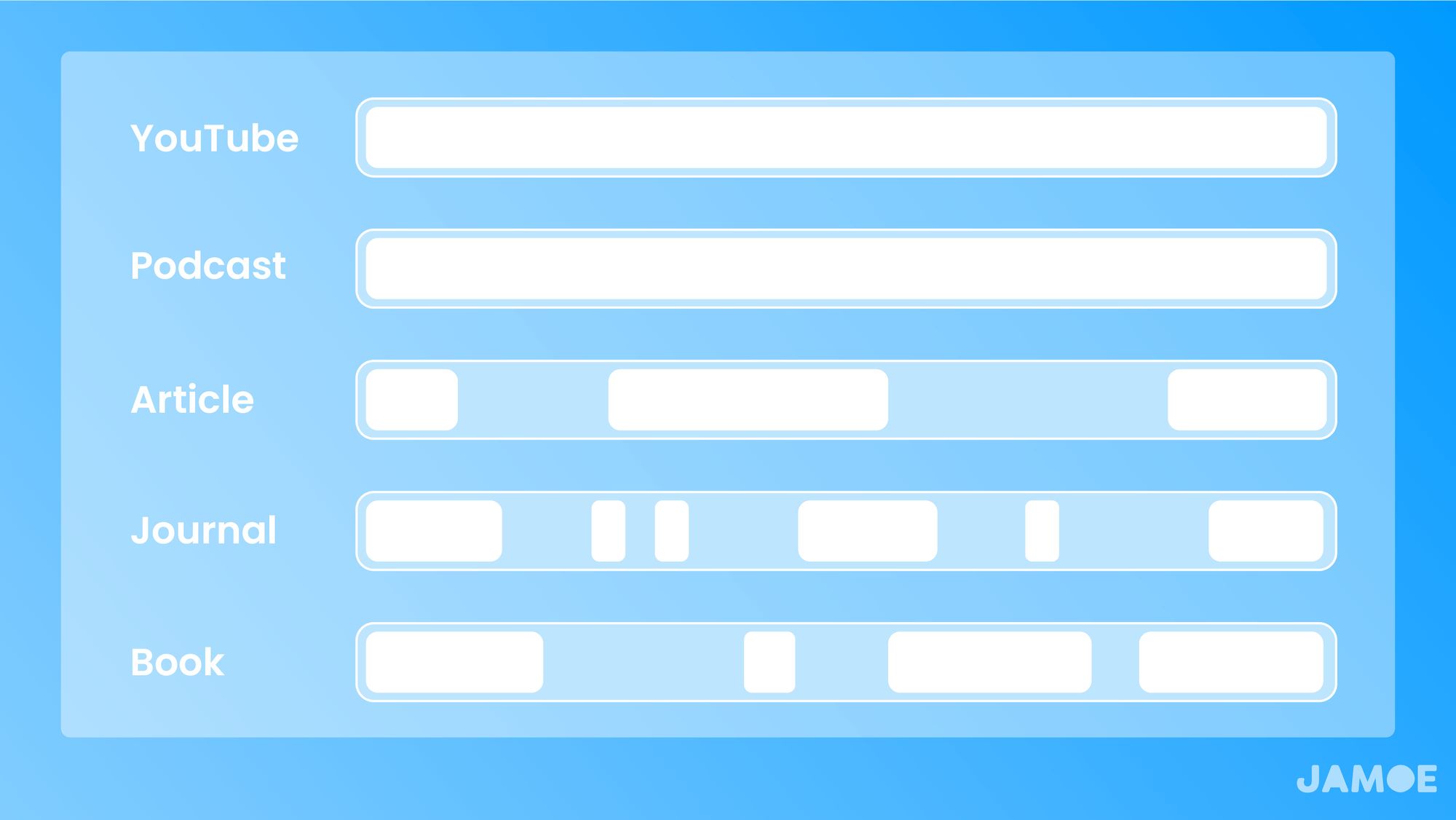

For our essay question, we started with the low-effort sources and then staircased our way to academic journals and books; we did so without shame. Often there is a pressure, self-imposed or otherwise, to look clever: we want to be seen reading dense books with complex equations. While we may look clever, this approach is more painful and slower.

Applying the Quit or Carry On principle

Wanting to be strategic with our time, we staircased our way to understanding. To give you an idea of how we put this into practice, below is a sample of the 17 sources we used and a map of how we applied the Quit or Carry On principle to find the most relevant parts, like when we flick through a cookbook. The result was a much more efficiently written essay[1].

- Video (10.05 min) – Universal Basic Income Explained

- Podcast (9.27 min) – What McDonald's Tells Us About The Minimum Wage

- Article (3,944 words) Yuval Noah Harari on what the year 2050 has in store for humankind

- Journal (21,651 words) – World Economic Forum: The Future of Jobs Report 2020

- Book (94,537 words) – Humans as a Service by Jeremias Prassl

Conclusion

Making sense of and solving unfamiliar problems is a daily ritual of the 21st century. Whilst every problem is unique, the General to Specific and Quit or Carry On principles offer a rock solid way for strategically moving from confusion to clarity.

Together they'll give you a foothold for understanding any topic by prompting you to build up a sturdy knowledge base. That will make what you're learning stickier, as you can use this base like how branches and leaves use the trunk of a tree to avoid being blown away.

Honing your ability to sense-make will leave you with what we believe is a more robust form of education: knowing what to do when you don't know what to do.

Footnotes

[1] For the curious amongst you, below is the final draft of essay's introduction. Despite the 3 day deadline, the essay offers a novel take on the question by challenging the relevance of the minimum wage as technology continues to advance:

Except from an Oxford essay: Should the minimum wage be abolished?

One purpose of the minimum wage is to prevent the exploitation of labour and another is to guarantee a minimum quality of life to those with minimum wage jobs. The nature of minimum wage jobs has changed drastically throughout the 20th century. The chimney sweep now finds himself behind a supermarket cashier and most farmers find themselves needing to work in factories instead. The force changing the nature of these minimum wage jobs is technological advancement. The transition from coal to gas made chimney sweeps unnecessary. Technology also made the farming process so efficient that we can now produce far more food with far fewer workers. The nature of minimum wage jobs in the 21st century will see similar changes. The chimney sweep who found himself behind a supermarket cashier is being made redundant as physical stores are shut down in favour of online shopping. Having been made redundant once again, what’s next for our chimney sweep-turned-supermarket cashier? It is commonly assumed that new jobs are created at a pace equal to or greater than the pace at which existing jobs are destroyed. However, we will argue that this assumption is under threat. Increasingly new technological innovations are destroying jobs, especially those done by minimum wage workers, far faster than new ones are being made. With that shown to be true, it will follow that the minimum wage should be abolished, as its role in providing the opportunity for a minimum quality of life to workers will also be made redundant. After all, the minimum wage is no comfort to the unemployable. To further support the abolishment of the minimum wage, an alternative will be offered that will be judged to be strictly better both during and after the transition to a large technologically unemployed class, universal basic income (UBI). By abolishing the minimum wage, the opportunity cost surrounding maintaining the policy can be redirected towards some form of UBI.